Faces of South: Omari Amili

After 8 and a half months in the Pierce County Jail many people, including his fellow prisoners and probation officers, expected Omari Amili, a South Seattle College R.I.S.E. Navigator, to end up back behind bars.

Studies by the US Department of Justice have shown that more than half of all state prisoners end up returning to prison within five years of their release. The implication being that people who have been incarcerated spend most of their lives in and out of correctional facilities. High recidivism rates can be attributed to a shortage in reentry programs, vocational skills training, educational and employment opportunities.

But Omari always had other plans for himself, and within 10 years of his release had graduated with his bachelor’s degree in Psychology and Self and Society from UW-Tacoma, and a master’s in Interdisciplinary Studies from the University of Washington.

This quarter, Omari will begin his new position with South Seattle College to help others follow in his footsteps, shunning the statistics and finding a path forward after incarceration. He will teach life skills to people who have recently been released from prison or on work release at local community corrections offices in Kent and Burien. Much of his teaching will focus on how to break old habits.

“Basically I’ll be teaching decision-making, and helping people make better choices so they don’t find themselves back in prison,” says Omari. “I’ll be introducing them to some tools and resources like the R.I.S.E. program at South, and get them thinking and analyzing situations from their past that they might encounter in the future.”

R.I.S.E. (Resources to Initiate Successful Employment), a pilot employment program at South, assists students and community members find employment through services in case management, job experience, and employment and training assistance.

Omari will work mostly with underserved populations from a wide variety of ages and backgrounds. He says breaking away from habitual criminal activity and negative lifestyles can be difficult, but his own experiences have helped him connect with students who might otherwise have tuned him out.

“Growing up, I didn’t know too many males that had a job, and many of them mistreated women. It’s easy to get a distorted perception about how to conduct yourself when everyone around you is living that lifestyle,” says Omari. “So for the students to see that I’ve been down before, they can relate to it, and it inspires them to see where I’ve came from and where I am now. To see a guy that got out of prison with a GED, who’s now a faculty member at South Seattle College, it opens their eyes to the possibilities.”

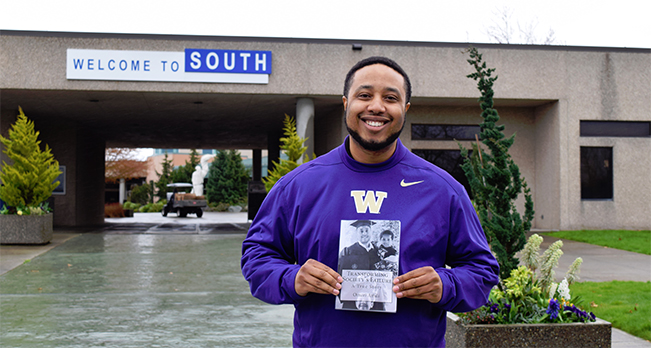

Inspiration is one of the messages Omari hopes to convey through his first book, “Transforming Society’s Failure,” which details his time growing up in poverty, his experiences in the criminal justice system and finally becoming a “productive member of society and a scholar following incarceration.”

“I decided to write the book because people need to know that you can get out of prison, turn things around, and do something positive with your life,” says Omari. “I wanted to get this story out there, whether someone is reading it in prison, a family member or someone who might work with people who got out of prison. We don’t need to make these people a member of a permanent underclass just because they got in trouble in their past. Let’s open up some doors and let’s provide some opportunities because they might be another Omari.”

Being in a community college setting isn’t new to Omari. After his release he applied to Pierce College and earned his associates degree before transferring to UW-Tacoma. For a student like Omari, with no experience in higher education and a criminal background, community college made achieving a degree and real possibility.

“For me it was the first time that I could see myself completing something,” says Omari. “To be able to go to classes and earn credits towards a degree, I was actually seeing progress and it gave me a positive identity as a college student. People weren’t looking at me as a convict or a felon, which plays a major role in your identity. I felt that I was part of a campus community. I feel the same way here at South Seattle College.”